“Bend the knee.” Perhaps largely influenced by the particular use of the expression in the popular books and video series, “Game of Thrones,” the notion of bending the knee before a power greater than oneself is fraught with quite unpleasant associations: self-abasement before a coercive force, humiliation, servitude… We can understand why such a gesture would stir up resistance, shame, and anger.

Yet, in the liturgy of Palm Sunday and again on Good Friday, we “bend the knee,” kneeling reverently and full of devotion as we acknowledge Jesus’ self-sacrificial death on the Cross. The experience, and I can only speak for myself, is entirely different. Not only am I freely entering into this ancient posture of respect, of deference, but I often find at those moments a strange, confused, yet overwhelming sense of gratitude welling up inside me. Why?

As you and I know, Palm Sunday serves as the initial, nearly cinematic step on a journey through the final and most intense week in the lives of Jesus and his disciples, and of the crowds who both follow and reject him. We, though, can barely follow let alone feel our way through the various encounters and events of these days because each one nearly overwhelms us with drama. We consider during Holy Week: the seemingly triumphant entry into Jerusalem; the preparation for Passover; the final instructions to the disciples; the last supper; the anguish and betrayal in the Garden of Gethsemene; and one seemingly endless night before the last day in the earthly life of Jesus. For me, it seems too much to take in, to sense, feel, and make sense of what happens from one Sunday to the next.

But this Palm Sunday, our liturgy provides a key to understanding, a lens to look through and help us to focus, a text that illuminates all the other texts. This Sunday, we read from the Letter of Paul to the Philippians, chapter 2. It is one of the most important “Christological” passages of the whole New Testament, as Paul expresses this affirmation of Jesus’ humanity and his divinity. He writes to one of his most cherished communities, a community filled with gentile converts who generously support Paul in his ministry, while at the same time, they are also experiencing persecution, division, and conflict among themselves. They are not so unlike ourselves at this moment in history.

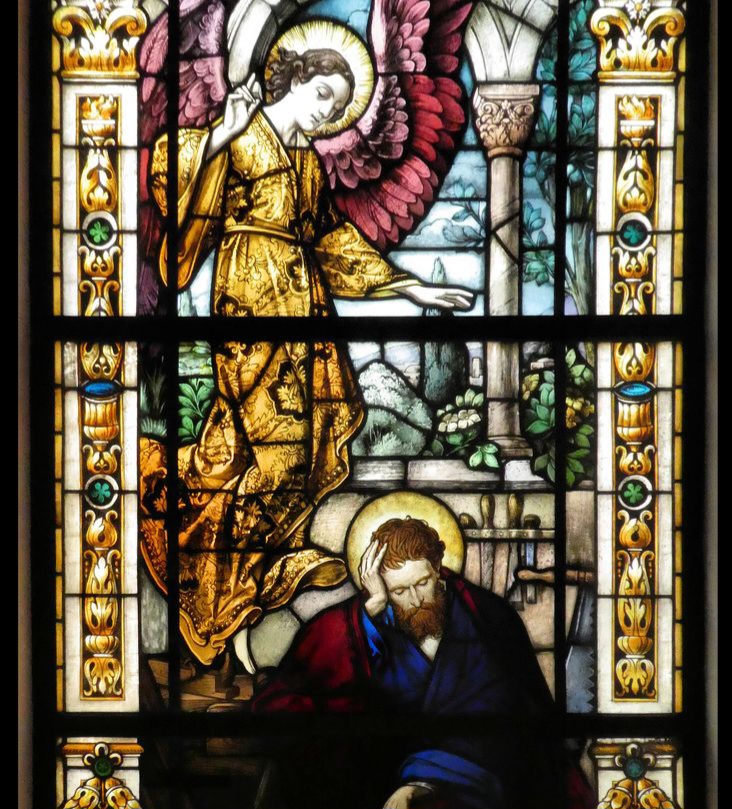

Paul desires more than anything to bring this community together around the example of Jesus, to console and strengthen them with the same spirit with which Jesus, the Christ, has consoled and strengthened him. In order to do this though, he does not inflate them with vain hopes or promises of exemption from their current trials and sufferings. Paul directs their attention to his Lord, who, though he was in the form of God, did not cling to any of the trappings of divinity: omnipotence, omniscience, omnipresence, invincibility… but rather, he emptied himself fully into his incarnation, this extraordinary humanity. And not only fully human, Christ goes further, taking the role of a slave on our behalf, lovingly laboring for our salvation with no end to his giving of himself. His obedience, his faithful and complete listening to and enacting of the will of his Father, is the expression of his freedom from sin and of total willingness to be his Father’s instrument. He doesn’t exempt himself from experiences of betrayal and abandonment, in order that he might take on fully what it can feel like at the extremes of our human condition. He even willingly accepts to become a victim of the cruelest form of execution to finally die as an outcast, a religious heretic, and a political criminal. And it is for this reason that God greatly exalts him, bestowing on him the name above all names, so that at the name of Jesus, every knee should bend, in awestruck devotion and unending gratefulness.

At the heart of this text is the humility of Jesus, the virtue perhaps most unpopular among us today. We see all around us what our resistance to this virtue means for us, for our cultures and societies, for our planet today. But the humility of Jesus, who does not grasp at the attributes of godhood- it is his humility that saves us. The humility we see from the moment he takes the stage at the beginning of this terrible and wondrous week. The humility of a man astride a small young donkey: not a proud warhorse, but a borrowed beast of burden. The humility of a man who loves his imperfect and squabbling friends, even bending to wash their feet. The humility of man who loves and saves his enemies, who spit on him and beat him, who reject and kill him. This is the humility of a child entirely devoted and trusting in his father, to save and redeem his life.

As we ponder the humility of Jesus this week, might we also consider how we might more fully accept our own humanity and find freedom from the pretenses of any attributes of divinity? In recent weeks, I’ve resisted and resented having to acknowledge my own grasping for divinity: my desire to have complete control over the circumstances in which I find myself, to be all knowing, to be exempt from pain, or from emotions I’d rather not feel. Yet at every turn, I hear God saying, look to my son, who did not grasp for such things, but rather, emptied himself humbly and lovingly for you. For you and you and you.

As we who have roles, responsibilities, authority, and so many forms of power, Paul’s focus on the humility of Jesus, this self-emptying into full humanity and service of others, might be for us a key to understanding, at least in part, the Paschal mysteries we contemplate this week. When, on Good Friday, we again are invited to kneel at the foot of the Cross, I pray that it is a moment of deep grace and gift for each of us. For it is the moment of our redemption.

A blessed and spiritually fruitful Holy Week to you all!